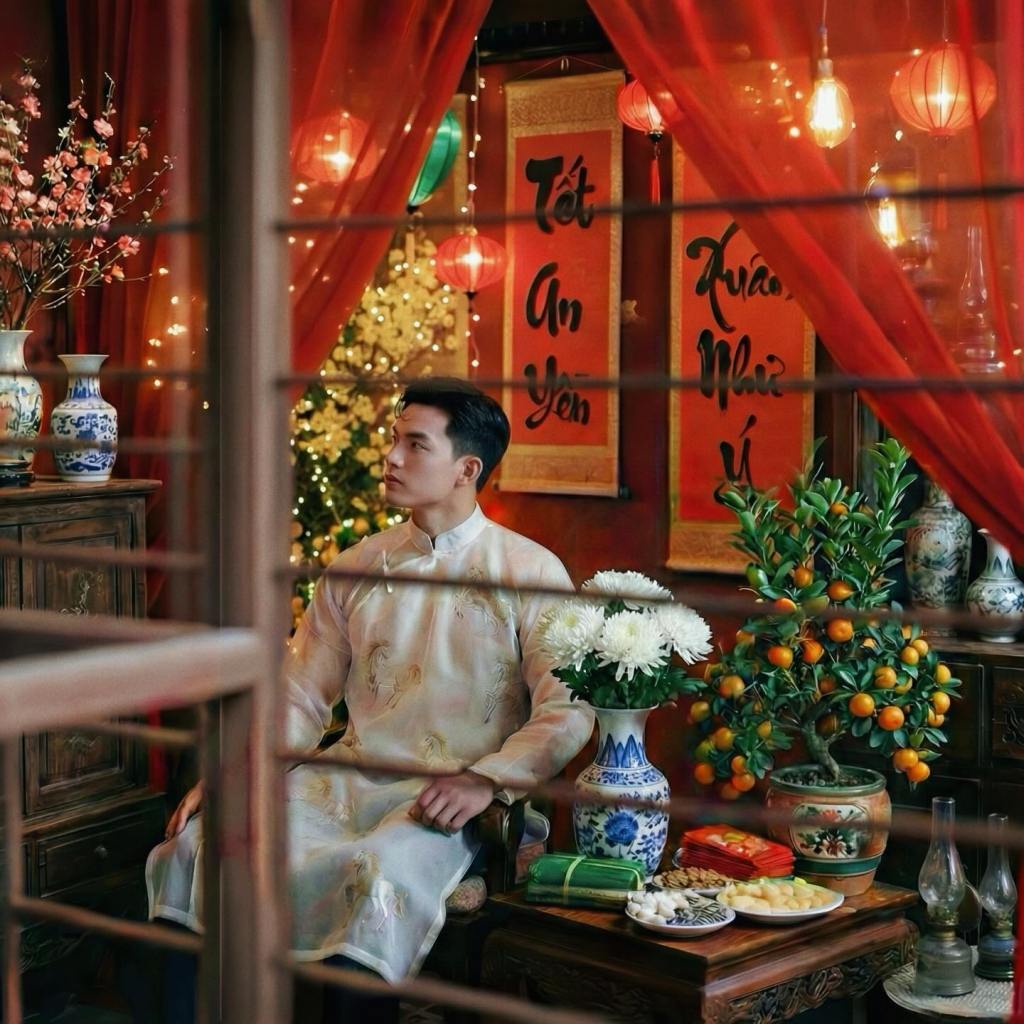

Thứ Sáu, ngày 20/02/2026 (Mùng 4 Tết).

Sáng nay, không khí trong các con ngõ Sài Gòn có chút trầm lắng hơn. Trước cửa mỗi nhà, người ta bày một cái lò nhỏ đỏ lửa. Những tờ giấy tiền vàng mã được thả vào, hóa thành tro bụi, bay lơ lửng trong gió xuân. Người ta gọi đó là lễ Hóa Vàng. Với nhiều người trẻ, đây có thể là mê tín. Nhưng với Tom, đây là nghi thức của Tình Thương.

“Tiền tệ” của Ký Ức Tại sao chúng ta lại đốt giấy tiền, quần áo giấy cho người đã khuất? Không phải vì ta tin rằng ở thế giới bên kia có siêu thị hay ngân hàng. Mà vì đó là cách duy nhất người sống có thể “chăm sóc” người mất. Khi Tom thả bộ quần áo giấy vào lửa, Tom thì thầm: “Ông ơi, năm mới ông mặc áo mới cho đẹp nhé.” Khi Tom đốt thỏi vàng giấy, Tom gửi gắm: “Bà ơi, bà đi đường xa về, có chút lộ phí phòng thân.” Ngọn lửa ấy chuyển hóa vật chất (giấy) thành tinh thần (sự an tâm). Nó làm cho người sống cảm thấy mình đã làm tròn đạo hiếu, và người đi xa cũng cảm thấy ấm lòng. Hóa vàng, thực chất là Hóa giải nỗi nhớ thương.

Bữa cơm “Tiễn Đưa” (The Farewell Meal) Mâm cơm cúng Mùng 4 thường đơn giản hơn Mùng 1, Mùng 2. Không còn quá nhiều sơn hào hải vị, mà là những món ăn thân mật, “đưa cơm” như canh măng, dưa hành. Cảm giác giống như bữa cơm chia tay người thân ra sân bay đi nước ngoài vậy. Vừa ăn vừa lưu luyến. Vừa ăn vừa dặn dò: “Ông bà về bên ấy nhớ phù hộ cho tụi nhỏ ngoan ngoãn, cho gia đạo bình an.” Khoảng cách Âm – Dương lúc này dường như bị xóa nhòa. Chỉ còn lại một đại gia đình đang ngồi quây quần, chia sẻ những giây phút cuối cùng của kỳ nghỉ lễ thiêng liêng.

Rượu nồng tưới tắt tàn tro Nghi thức kết thúc bằng một hành động rất đẹp: Tưới chén rượu cúng lên đống tro tàn. Xèo… xèo… Khói trắng bốc lên nghi ngút. Hơi rượu thơm nồng hòa quyện với mùi tro. Người xưa tin rằng rượu sẽ làm cho vàng mã “thiêng” hơn, giúp ông bà nhận được nguyên vẹn. Nhưng Tom nhìn thấy ở đó một triết lý khác: Sự Buông Bỏ (Letting Go). Ngọn lửa cháy rực rỡ rồi cũng tàn. Cuộc vui nào rồi cũng đến lúc tan. Tết đã đến, Tết đã vui, và giờ Tết phải đi để nhường chỗ cho những ngày lao động hăng say. Chúng ta tiễn ông bà đi không phải để lãng quên, mà để gói ghém lại những kỷ niệm đẹp, cất vào tim, và bước tiếp vào năm mới với một tâm thế vững vàng.

Lời nhắn Mùng 4: Hôm nay, khi bạn hóa vàng, đừng đốt vội vã cho xong việc. Hãy đốt từ từ, từng tờ một. Nhìn ngọn lửa liếm trọn tờ giấy, chuyển sang màu đỏ rực rồi tan thành tro xám. Đó là một bài thiền về sự Vô Thường. Mọi thứ vật chất rồi sẽ tan biến, chỉ có Tình Yêu và Lòng Biết Ơn là còn lại, bay cao theo làn khói kia. Tiễn ông bà về trời, và hẹn gặp lại mùa Xuân năm sau!

The Gold Burning Ritual on the 4th: A Lingering Farewell & The Smoke Carrying Wishes

Friday, February 20th, 2026 (4th Day of Lunar New Year).

This morning, the atmosphere in Saigon’s alleys is a bit more subdued. Before every house door, a small red stove is set up. Votive papers are dropped in, turning to ash, drifting in the spring breeze. People call this the Gold Burning Ritual(Lễ Hóa Vàng). To many young people, this might seem like superstition. But to me, this is a ritual of Love.

The “Currency” of Memory Why do we burn paper money and paper clothes for the departed? Not because we believe the other world has supermarkets or banks. But because it is the only way the living can “take care” of the dead. When I drop a paper shirt into the fire, I whisper: “Grandpa, wear this new shirt for the new year to look handsome.” When I burn a paper gold bar, I send a message: “Grandma, you have a long way back, here’s some pocket money for the road.” That fire transforms matter (paper) into spirit (peace of mind). It makes the living feel they have fulfilled their filial duty, and the departed feel warmed. Gold burning is essentially Dissolving the longing.

The Farewell Meal The offering meal on the 4th is usually simpler than on the 1st or 2nd. Not too many delicacies, but intimate, comforting dishes like bamboo shoot soup, pickled onions. It feels like a farewell meal before seeing a relative off to the airport to go abroad. Eating while lingering. Eating while reminding: “Grandparents, when you return over there, please bless the kids to be obedient, and the family to be peaceful.” The distance between Yin and Yang seems blurred at this moment. Only a large family remains, sitting together, sharing the final moments of the sacred holiday.

Wine Poured Over the Ashes The ritual ends with a beautiful action: Pouring the offering wine onto the pile of ashes. Sizzle… sizzle… White smoke rises thickly. The fragrant steam of alcohol blends with the smell of ash. The ancients believed wine makes the offerings “sacred,” ensuring ancestors receive them intact. But I see another philosophy there: Letting Go. The fire burns brightly and then fades. Every party must come to an end. Tet came, Tet was joyous, and now Tet must go to make room for days of hard work. We send the ancestors off not to forget them, but to pack up the beautiful memories, store them in our hearts, and step into the new year with a steady mindset.

New Year’s Note (Mùng 4): Today, when you burn the offerings, don’t rush just to get it done. Burn slowly, one sheet at a time. Watch the fire lick the paper, turning it bright red before crumbling into gray ash. It is a meditation on Impermanence. All material things will vanish, only Love and Gratitude remain, rising high with that smoke. Farewell to the ancestors returning to heaven, and see you again next Spring!

Leave a comment